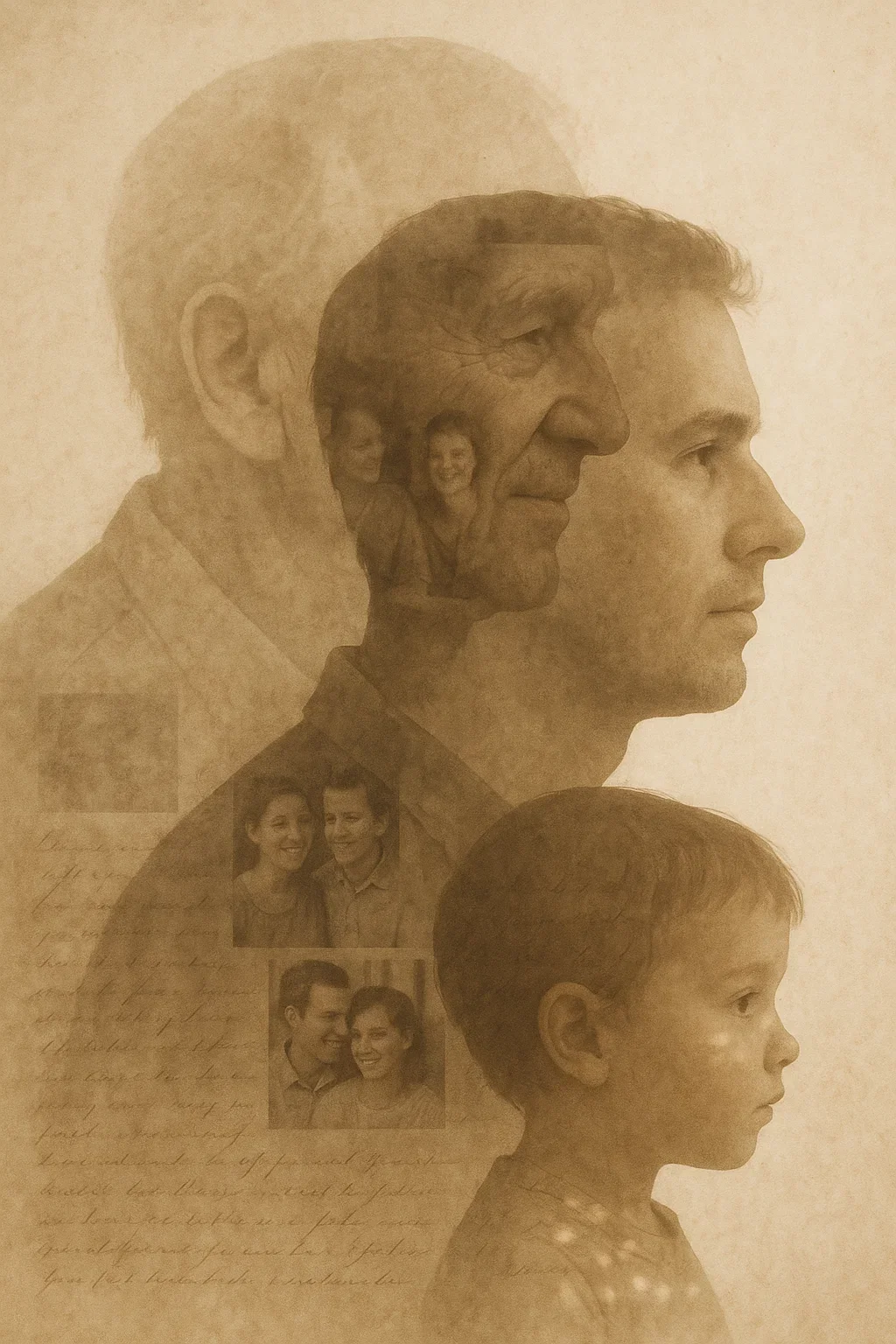

The Weight of Legacy

Legacy Isn’t Just About What We Leave Behind…

When I think about legacy, I notice how often the conversation centres on what we want to leave behind; our accomplishments, values, or dreams for our children. But what we don’t talk about nearly enough is the other side of that coin: legacy burdens. These are the unspoken weights passed down through families: beliefs, expectations, traumas, or patterns, that shape the way we live, love, and relate to one another. Unlike the legacy we aspire to create, these burdens are rarely chosen, yet they influence us all. I want to explore this hidden inheritance to shed light on what it means to carry it, and perhaps, how we can begin to set it down.

We inherit more than eye colour, family recipes, or old photo albums. We inherit stories… some told, some silenced. We inherit expectations, fears, and patterns of relating that were shaped long before we arrived. In psychology, this phenomenon is often referred to as legacy burdens: the emotional, psychological, and sometimes even spiritual weight passed down from one generation to the next.

Legacy burdens are not just “family baggage.” They are unprocessed grief, cultural traumas, or rigid beliefs that seep into the foundation of identity. The field of epigenetics even suggests that trauma can leave chemical marks on our DNA, influencing stress responses across generations. In short, what our ancestors endured doesn’t simply vanish when the moment passes, it often lives on in us.

But legacy burdens don’t look the same for everyone. To understand this more deeply, I thought it would be insightful to explore legacy burdens through two lenses: the immigrant family and the non-immigrant experience.

The Invisible Inheritance We All Carry

Legacy Burdens In Immigrant Families

For many immigrants, the journey to a new country is driven by survival, opportunity, or the dream of a better life. Yet along with hope comes hardship. Leaving behind home means leaving behind belonging, extended family, cultural roots, and often safety. Parents and grandparents carry the invisible weight of displacement, sacrifice, and loss; those burdens often find their way into the next generation.

Children of immigrants frequently grow up in what psychologists call a “double bind of identity.” On one side, they inherit their parents’ unspoken fears: Don’t stand out. Don’t waste opportunities. Don’t forget what we gave up for you. On the other, they face the pressures of assimilation: Fit in. Succeed. Prove you belong.

Research on the “intergenerational transmission of trauma” shows that when the first generation suppresses grief or fear to survive, the second generation absorbs it as an undercurrent of anxiety, hypervigilance, or perfectionism. A child may not know the full story of their parents’ sacrifices, but they feel the weight of an expectation: We endured, so you must excel.

One powerful example of legacy burdens at work is academic overachievement among immigrant children. Behind this pattern are stories of parents who left everything behind: home, language, extended family, with the hope their children would have opportunities they themselves never had.

Research supports the idea that those hopes aren’t idle. In one Canadian study of 783 children from immigrant families, higher educational expectations and aspirations from parents were strongly linked to stronger school performance, even after accounting for background and socioeconomic status. Across the U.S., studies show that immigrant adolescents often outperform their non-immigrant peers not because they have more resources, but because home culture, peers, and parents together emphasise education, hard work, and persistence.

Part of this is also “immigrant optimism”, the belief deeply held by many first-generation parents that their children must not just survive, but thrive. Combined with educational selectivity (as many immigrants arrive with strong motivation or prior education), these pressures become a kind of inheritance. The child inherits not only support and belief, but also the burden: that their success must repay what was lost, and that failure is not simply personal, it touches the history and hope of those who came before.

This doesn’t always play out as noble strength, sometimes it manifests as anxiety, perfectionism, or internal conflict. But it helps explain why many immigrant children tend to excel in school. Their achievements are often fuelled by love, loss, duty, and tremendous unseen weight.

Yet for many children of immigrants, success doesn’t feel like freedom; it feels like obligation. The very achievements that are meant to symbolise hope and progress often become another layer of responsibility. Academic and professional success are rarely things they can simply enjoy for themselves; instead, they are seen as collective victories that must serve the family.

With success comes a new kind of weight: the expectation to give back, to provide, to send money home, or to fund the dreams their parents had to set aside. This sense of duty is often accompanied by deep gratitude, but also by quiet pressure. Their success is not entirely theirs to celebrate; it belongs to the family, to the sacrifices made long before they arrived.

And when that success doesn’t come easily, or at all, shame seeps in. Within many immigrant families and cultures, failure carries a social and emotional cost that extends beyond the individual. Not doing well can feel like dishonouring one’s lineage, as if all the sacrifices were for nothing. The child internalises this shame, sometimes turning it inward as self-blame or a relentless drive to prove their worth.

Even when they do achieve, the question often lingers: Do I deserve this? How can I take pride in my accomplishments when my parents worked harder, endured more, and had fewer opportunities? It’s a quiet guilt, the sense that their success came “too easily” compared to their parents’ struggle. This self-doubt can erode confidence, making it hard to recognise one’s own effort, resilience, and talent.

This is often where the identity crisis begins. Between gratitude and guilt, pride and pressure, many second-generation immigrants struggle to locate their own desires. What do I want, separate from what my parents hoped for me? Is it selfish to choose differently after everything they gave up? When survival and sacrifice have defined a family’s story, there’s little room to dream for oneself.

In this way, legacy burdens aren’t just emotional, they become existential. The child inherits not only their family’s history but also their unresolved longing and unfinished dreams. Success, then, is never simply about achievement; it’s about carrying forward a legacy that is both a gift and a weight.

Legacy Burdens In Non-Immigrant Families

For many non-immigrant families, legacy burdens are woven into the fabric of normalcy. They’re not always born from trauma or displacement, but from continuity; from the pressure to uphold a family identity that has existed for generations. It might sound like pride in tradition or loyalty to family values, but beneath it often lies an unspoken rule: don’t disrupt what’s been built.

In families that have lived in the same culture or country for generations, legacy burdens often arise from stability itself. When there’s a long line of tradition, career paths, or social standing to maintain, the pressure is not to create opportunity but to preserve it. Success, in this context, means protecting what came before: the family name, the reputation, the unspoken standard of “how things are done.”

Some carry the burden of perfectionism, the unrelenting need to succeed, not out of ambition, but out of duty. The family may never demand it outright, yet the expectation hums beneath the surface: We’ve always done well, so you must too. This can lead to lives that appear accomplished from the outside but feel disconnected within, as though one’s worth is constantly being measured against an invisible family standard. Think of wealthy families, multigenerational business owners, or those with long-standing professional legacies… where success feels less like a choice and more like an inheritance.

Others inherit stories of stoicism and self-reliance: generations that endured quietly, who “got on with it” without complaint. While this resilience is admirable, it can also make emotional honesty difficult. Grief, vulnerability, or failure become things to hide; not because the family doesn’t care, but because they were never given the language or permission to express them. The result is a kind of generational emotional silence: the heart learns to whisper what the mouth was never allowed to say.

And then there are the families where identity itself becomes a legacy burden. The expectation to mirror the beliefs, politics, religion, or way of life of previous generations can make individuality feel dangerous. The cost of authenticity becomes the fear of rejection. Breaking away, even gently, can feel like betrayal. In these cases, the burden isn’t one of survival, but of continuity: the pressure to keep being who the family has always been, even when the world has changed.

In this way, legacy burdens in non-immigrant families may not bear the visible scars of displacement or loss, but they can shape the emotional landscape of a life. They influence the choices we make, the truths we silence, and the parts of ourselves we keep hidden to preserve love or belonging. The result is often the same inner conflict, the tension between belonging and becoming, between honouring where we come from and discovering who we are.

The Weight We Carry And How We Set It Down

For me, I’m privileged to say I don’t carry the heavy weight of a legacy burden, even though I come from an immigrant background and have lived in different countries and cities across Europe. My mum never pressured me to excel in school; perhaps because I naturally loved learning and was self-driven. She never dictated what I should study or who I should become. Instead, she gave the freedom to explore, to evolve, to belong to myself in every new environment I found myself in.

My burden, if I can even call it that, came from within. In my late twenties and early thirties, I began to feel a quiet guilt that my success had come “too easily”. It wasn’t tied to my immediate family, but to something larger, a kind of inherited empathy, or perhaps survivor’s guilt. I would think of other immigrant families struggling to find their footing, of children more talented or hardworking than I was, and wonder: why me? Why should my path be smoother when theirs was filled with obstacles?

Over time, I realised that this guilt was rooted in love; in a deep sense of duty to care about my wider community, to carry their stories alongside my own. But I’ve also learned that compassion doesn’t require self-erasure. I can hold empathy for others while still honouring the effort, curiosity, and resilience that shaped my own path. My achievements were not accidents of circumstance; they were the result of showing up for growth again and again, of choosing possibility over limitation.

It wasn’t a legacy burden in the traditional sense, but it revealed something important about the ways we are all interconnected. Whether we carry the visible weight of our family’s past or simply feel the echoes of what others have endured, we all live within the ripple of legacy. Some inherit survival; others inherit expectation. Some inherit silence; others inherit guilt. But all of us, in one way or another, inherit something - and in learning to understand it, we give ourselves permission to transform it.

The work, then, is not to reject our legacy, but to understand it; to recognise what is ours to carry, and what can finally be set down. Let’s carry our history with grace, not weight. To move forward, not out of guilt or duty, but from a place of freedom, gratitude, and self-understanding.